On June 29, 2020, the Government of India issued a directive to ban 59 apps of Chinese origin, based on the grounds that these apps “are engaged in activities which [are] prejudicial to [the] sovereignty and integrity of India, [the] defense of India, security of [the] state and public order”.

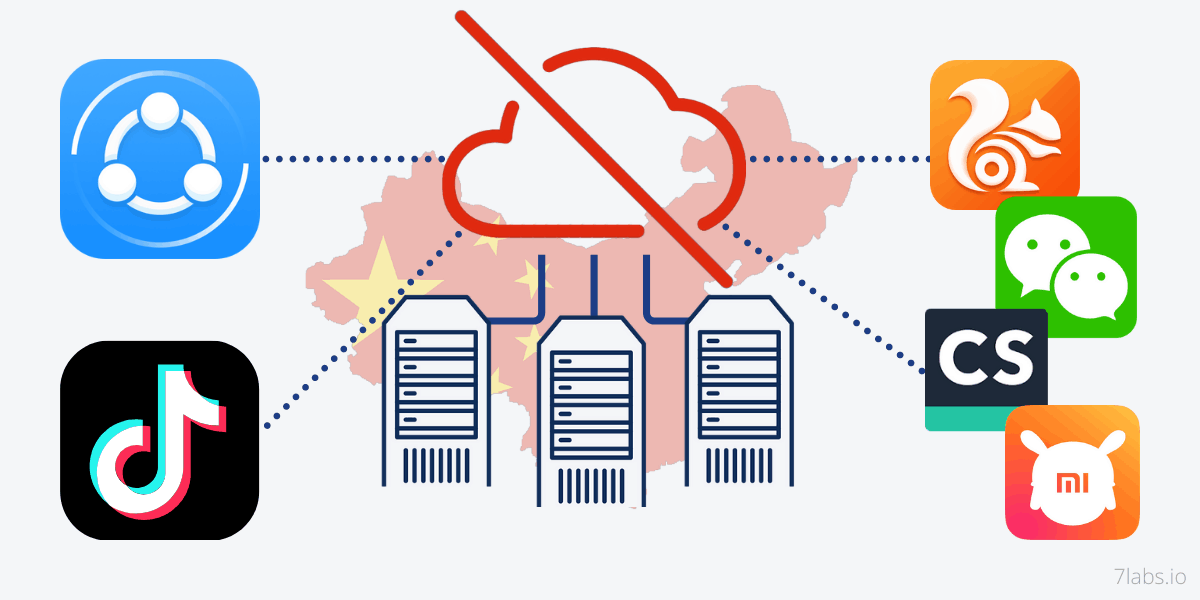

The ban included popular app titles, including TikTok, WeChat, CamScanner, SHAREIt, UC Browser, and others; many of which have a significant user-base in India. TikTok had especially gained popularity in the subcontinent, particularly among young audiences, for its short-form videos and unique effects.

The app has more than 200 million users in India, making the country its largest overseas market. According to mobile insights firm Sensor Tower, the app has been downloaded more than 2 billion times globally, and India accounts for over 611 million of them.

Less than a day after the ban was imposed, TikTok blocked its access to users in India in compliance with the Indian Government directive and removed its apps from the App Store and Google Play Store. Common workarounds to unblock the service, like sideloading the app, switching DNS entries, or accessing the service through VPNs aren’t working as expected.

Even if you are able to launch the website or app from India, you’ll be redirected to a page or pop-up where it says the following:

Dear Users,

On June 29, 2020 the Govt. of India decided to block 59 apps, including TikTok. We are in the process of complying with the Government of India’s directive and also working with the government to better understand the issue and explore a course of action.

Ensuring the privacy and security of all our users in India remains our utmost priority.

TikTok India Team.

Additionally, the Department of Telecommunications (DoT) has also ordered the mobile operators and ISPs to block the listed services with immediate effect.

Why India banned 59 Chinese apps including TikTok, WeChat, SHAREIt, etc.

Just before the ban was imposed on June 29, the Government of India had received an advisory from intelligence agencies to ban 53 apps with links to China, citing privacy and security concerns.

Chinese apps & their controversial practices

TikTok and the other apps on the ban list are known for having ambiguous privacy policies and implementing questionable data practices. They have evidently been collecting user data in secret and been uploading them to servers in China.

In November of 2019, an individual in the US sued ByteDance (the parent company behind TikTok) for secretly harvesting personally identifiable user data and sending it to China. The lawsuit also accused them of uploading draft (recorded but unpublished) videos without the user’s consent and having “ambiguous” privacy policies.

A few days back, TikTok, among other apps, were caught snooping the smartphone’s clipboard data, thanks to a new feature in iOS 14 developer beta. Reading clipboard data can be dangerous, as we often copy sensitive data on our devices, including passwords, addresses, contact numbers, and more. If apps are reading clipboard data, they might be able to access sensitive and private information.

While some apps have legitimate reasons to access the system clipboard, apps that have no text field to enter text have no reason to read the clipboard, according to security researchers Talal Haj Bakry and Tommy Mysk.

TikTok has also been in the news lately for allegedly allowing users to post videos that involve hate speech, religious discrimination, misleading information, etc., often used to influence public opinion and cause political unrest.

Camscanner is another app in the banned list that included malicious code, as found by researchers at Kaspersky Lab earlier last year. The app used to be a legitimate document scanning app for quite some time, but later, it started shipping with an advertising library containing a malicious module. This malicious module is a Trojan dropper, which can extract and run other malicious modules from an encrypted file included in the app’s resources.

The app was removed from Google Play Store promptly after the report was published, and made a comeback later in September 2019. Currently, the app is no longer available on the App Store and Google Play Store in India, but existing users might still be able to use it.

In 2017, the Alibaba-owned UC Browser came under the scrutiny of the Indian Government for allegedly sending data from the users’ smartphones to servers in China. The complaint also stated that the app retained control over user data even after it was uninstalled from the device, through secret DNS configuration settings.

SHAREIt has been a popular file-sharing app, especially among Android users, letting you wirelessly transfer media files and other data from one phone to the other. However, security researchers have found severe implementation flaws in the Android version of the app that allows hackers to steal data.

According to the researchers, even though the vulnerability was patched, the app developers did not provide them the patched version, along with other details for public disclosure. The researchers also mentioned that communication with the SHAREIt team wasn’t a good experience; they weren’t cooperative and often respond late to messages.

As of now, the app has been removed from the Indian App Store and Google Play Store, but reports suggest that the app is functional for the existing users. This might be because it’s designed to work offline on local Wi-Fi networks.

The above are just a few examples of how these Chinese apps may be collecting user data, often without consent. While some of these app-makers have released official statements that they take user privacy seriously and would never share the data of Indian citizens with China, it’s difficult to understand if they can really protect the data from Chinese authorities, as long as they are operating from China.

As per the National Intelligence Law of China, 2017 (Article 14, 16), any citizen of China (which includes app developers) is obliged to assist Chinese authorities, Public Security and State Security officials in a wide range of “intelligence” work, including sharing of users’ personal data collected by the app developers.

The fact that a foreign government entity might exercise control over the personal data of Indian citizens poses a threat to both user privacy as well as national security.

Pre-installed apps, alternate app stores, and ad personalization

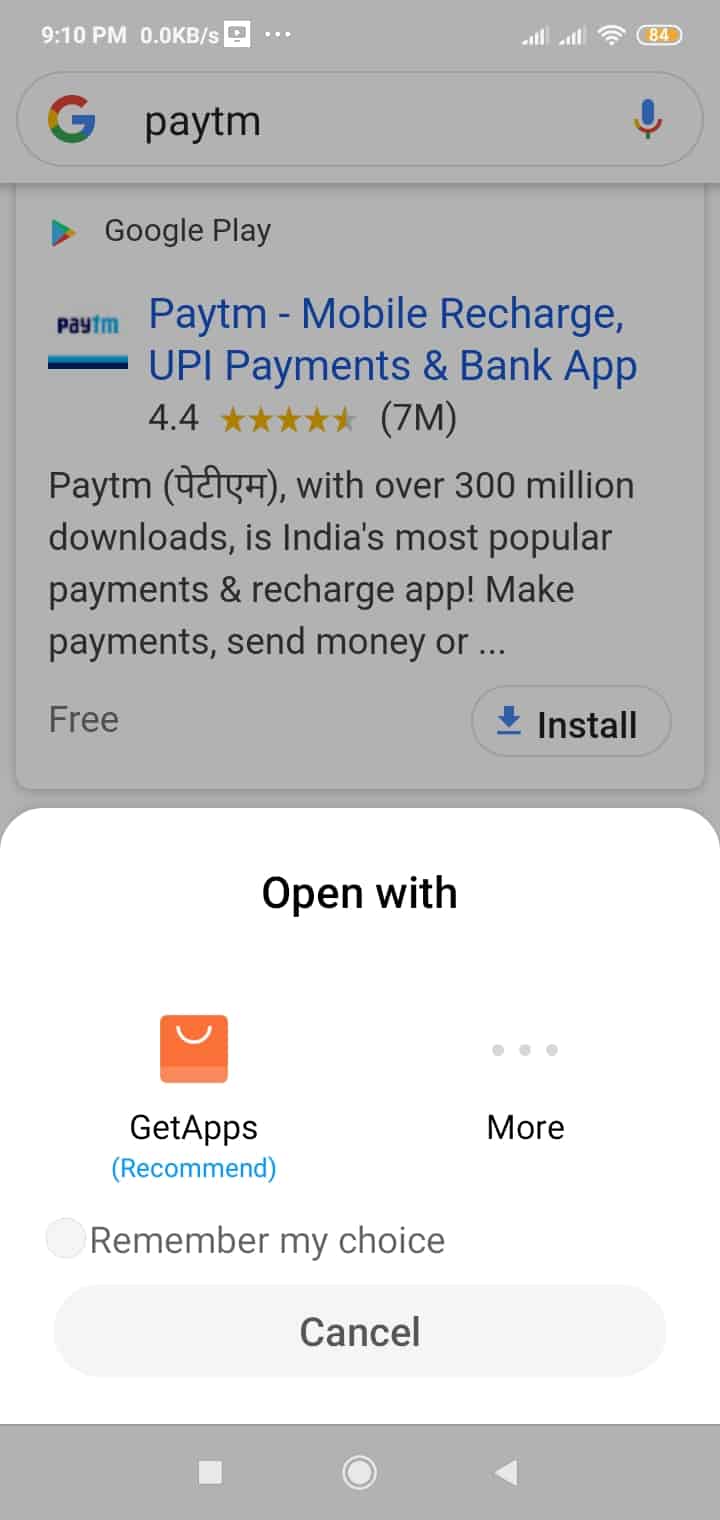

Chinese smartphone brands like Xiaomi, Oppo, Vivo, etc., which have significant market share in India, usually ship with pre-loaded apps and alternate app stores. These smartphones often implement certain practices that encourage users to install popular apps like Facebook, WhatsApp, etc., from their alternate app stores instead of the official Google Play Store. Even if a user searches for the app in Google and clicks on the Play Store Install button from the search results page, the experience is designed to ultimately redirect them to the alternate app store.

GetApps, Xiaomi’s “official” Google Play Store alternative is advertised as a “safe and reliable” way to get apps installed on your device. You’ll find similar descriptions of other alternate app stores offered by smartphone manufacturers. Top apps like Facebook, WhatsApp, Instagram, and others have been downloaded more than 50 Million times from GetApps, according to their own numbers.

Now, these alternate app stores are most likely controlled by the respective phone manufacturers. And it’s a genuine concern why these companies want the users to install apps from them instead of the official Google Play Store.

Not too long ago, cybersecurity researcher Gabi Cirlig found that his activities in Xiaomi’s default web browser and other Xiaomi software were being aggressively tracked. And the tracking continued even when he was using the browser’s private (incognito) mode.

Moreover, Xiaomi was apparently collecting additional data, including folder opens and screen swipes. All the data was allegedly packaged up and being sent to servers in Singapore and Russia, though the corresponding web domains were registered in Beijing.

Even though you are paying upfront for your smartphone, these companies are still trying to monetize your experience through aggressive advertising campaigns on their devices. Worse, some of the pre-installed apps may ask for unneeded or dangerous permissions under the pretext of serving you “personalized ad experiences”, which is just fancy talk for more tracking. It does not favor user privacy and security.

We have seen in the past how mass user-data collection and manipulation could be used to influence important political decisions. And it’s certainly within India’s interests to ban these apps, even permanently, under concerns of national security.

And though banning these apps might have been a great decision to limit further misuse of data, it also begs for the need for stronger data privacy and protection laws in India – ones that don’t compromise with Internet freedom.

The Impact: An uncertain future for indie creators & users

The sudden ban on Chinese apps, especially TikTok, has left Indian content creators and users surprised. The TikTok content creators of India, who used the platform as a revenue source through paid partnerships, have suddenly been left stranded and looking for an alternative platform. For many creators young and old, TikTok was a reliable (sometimes the only) source of income. And it certainly is going to be difficult for them to find solid ground again.

And what about the millions of Indian users who have invested in decent performing smartphones at affordable rates from companies like Xiaomi, Huawei/Honor, Oppo, Vivo, Realme, etc.? These are all primarily Chinese brands, and if the Government of India decides to ban operations of any of these brands within the country citing privacy and security concerns, the users might be left out on after-sale services, or worse, the devices might even cease to work reliably.

The fine line between Security and Censorship

Even though blocking access to apps and services through a ban or enforcement might seem like an obvious solution against questionable intent, it leaves the field open for misuse of power and censorship in the absence of well-defined data protection and privacy laws. Consequently, the situation raises serious concerns about the future of Internet freedom in India.

The need for stronger data protection & privacy laws

For the last few years, the Indian Government has aggressively pushed the country towards adopting digital standards and motivating users to go online. But, despite the “Digital India” initiative, the country still lacks extensive data protection laws that focus on enabling growth, while protecting the individual’s privacy.

Probably, a better way to handle the misuse of user data is to frame strong data protection and privacy regulations that service providers need to follow strictly in order to operate within the country, as well as letting users explicitly opt-in for data sharing. This usually puts the burden of compliance on the app developers and proactively minimizes data theft.

We’ve already seen good examples of laws implemented in other countries, which protect user privacy and security without taking away Internet freedom. The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) is a regulation for the European Union (EU) and the European Economic Area (EAA), created in 2016, centered around data protection, privacy, and consent. It encourages digital service providers in the EU region to provide users with more control over their personal data. In 2018, the state of California passed a similar law called the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) that focusses on protecting user data from being misused by businesses.

These laws generally dictate that to collect and use personal data, an app or service needs to get the consent from the user, after clearly stating what personal data is being collected, from what sources, how it’s intended to be used, where it is transferred, and how long the data is stored. It also mandates services to allow users to download or delete their data as required. The parties that collect or manage personal data are also obliged to protect it from misuse or exploitation and to uphold the rights of the data owners; failing to do so would attract penalties.

Thus, with these laws in place, it’s usually in the interest of app developers and service providers to responsibly collect and manage user data with due user consent, and to avoid misusing it and/or selling it to third-parties. The respective Governments don’t need to ban any service explicitly, and app developers need to abide by the law in order to stay operational. It’s a win-win situation.

Right now, India’s app ban is a workaround against the access and misuse of user data by foreign authorities. The ban could also motivate indigenous developers to create home-grown alternatives to popular Chinese apps.

But a regulation like GDPR or CCPA in India would protect the privacy of the users without compromising on Internet freedom.

In the aftermath of the TikTok ban, millions have already migrated to alternative “Made in India” platforms. Only time will tell whether any of these alternatives can gain enough traction to compete with TikTok in terms of popularity.